Keywords: David James

There are more than 200 results, only the first 200 are displayed here.

-

ECONOMICS

Fake news aside, increasingly, we live in a world of fake figures. There is a cliche in management that 'what gets measured gets done'. In public discourse that might be translated to 'what gets measured is considered real'. One obvious fake figure is GDP, which is taken as a measure of national wellbeing. In fact, it is just a measure of transactions. If money changes hands because something disastrous happens then GDP will rise. That is hardly an indicator of national wellbeing.

READ MORE

-

ECONOMICS

- David James

- 04 April 2017

13 Comments

It is increasingly evident how pernicious the privatisation myth is. Two recent examples have underlined it: the failings in Australia's privatised energy grid and the usurious pricing in airport car parks. Both demonstrated that it is folly to expect a public benefit to inevitably emerge from private profit seeking. The purpose of government funded public infrastructure is not to make profits but to lower the cost of doing business, sometimes called the socialisation of the means of production.

READ MORE

-

ECONOMICS

- David James

- 07 March 2017

17 Comments

Witnessing the debate over Sunday penalty rates, an intriguing pattern of thinking emerged. It can be characterised as a microcosm/macrocosm duality. Those arguing for lower Sunday wage rates demonstrate their case by talking about individual businesses, the micro approach: 'Many businesses would love to open on a Sunday and if wage rates were lower, they would. Unleash those businesses and greater employment will follow.' Superficially impressive, this does not survive much scrutiny.

READ MORE

-

ECONOMICS

- David James

- 07 February 2017

10 Comments

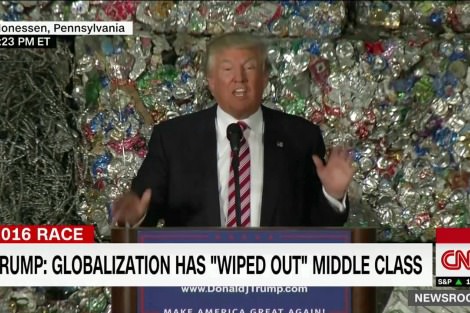

Many defenders of globalisation express frustration at the rise of Trump and what they see as an ignorant and self-defeating backlash against its virtues. But they have no answer to the most pressing question: Is the global system there to serve people, or are people there to serve the global system? They also never address a central contradiction of globalisation: that capital is free to move, but for the most part people are not, unless they belong to the elite ranks.

READ MORE

-

ECONOMICS

- David James

- 21 November 2016

9 Comments

The idea that machines will replace humans, transforming the work force, is far from new. As technology develops at an accelerating pace, there is growing concern that new social divisions are emerging. While there are signs of deepening social divisions between the rich and the rest of the working population, previous predictions of a collapse in employment have proven to be wrong. This is largely because a confusion arises from conflating production and transactions. They are not the same thing.

READ MORE

-

INTERNATIONAL

- David James

- 10 November 2016

17 Comments

The first step for a business person is to make the sale, usually by over-promising and tapping into the emotional triggers of the customer. That is what Trump did. Over and over, he assured everyone that electing him would be 'fantastic'; he would deliver; customer-value is in the bag. The next step, once the sale is made, is for a hard financial logic to be applied. Trump's hype will be, at the very least, toned down. Once the customer has coughed up, business people typically become extremely pragmatic.

READ MORE

-

ECONOMICS

- David James

- 10 October 2016

2 Comments

The strategy of the Big Four banks' appearance in parliament was clear enough. Blame the whole thing on a need to improve impersonal 'processes', imply that there have been a few bad apples but overall things are fine, and promise to do better in the future. The greatest challenge was probably to hide the smirks. A royal commission is being held up as an alternative, and no doubt it would be more effective. But a royal commission would not address the main issue.

READ MORE

-

ECONOMICS

- David James

- 13 September 2016

18 Comments

The argument that putting government operations into private hands ensures that things will run better and society will benefit is not merely a stretch; it is in many respects patently false. The argument is based on the claim that the market always produces superior price signals. Yet one area where private enterprise definitely fails is long term stability. If there is an expectation that a privatised service should last in the long term, and usually there is, then selling it to business is a bad choice.

READ MORE

-

INTERNATIONAL

- David James

- 09 August 2016

15 Comments

The main legislative catalyst for the GFC was the repeal, in 1999 by Bill Clinton, of the Glass Steagall Act, which had prohibited commercial banks from engaging in the investment business. This allowed the investment banks to indulge in the debauch of financial invention that almost destroyed the world's monetary system. Trump has made the reinstatement of Glass Steagall official policy. Should that happen, it could be the most beneficial development in the global financial system for decades.

READ MORE

-

ARTS AND CULTURE

- Tim Kroenert

- 05 August 2016

The interviewees regard Vertigo with awe, waxing lyrical about its psychosexual subtext; but not a word is said about the inherent misogyny of a film that is explicitly about a man's objectification of a woman. The film's most interesting segment however concerns the pre-eminence of guilt in Hitchcock's films, and the role it plays in shaping human activity. This, says Martin Scorsese (a filmmaker similarly preoccupied with guilt and sin), may define Hitchcock as an essentially Catholic filmmaker.

READ MORE

-

ECONOMICS

Had Greece decided to exit the EU last year the consequences would have been far greater than Brexit, because Greece uses the euro, whereas Britain has the pound. British interest rates are not set in Brussels, they are set by the Bank of England. And it has an independent fiscal and budgetary system, to the extent that it is possible. The British government has been imposing 'austerity' measures because it subscribes to neoliberal orthodoxy, not because it is being told to do so by Brussels or Germany.

READ MORE

-

ECONOMICS

There is little doubt that the means to dramatically reduce the amount of pollution produced by developed economies is already theoretically available. It is perfectly possible to redesign industrial systems so that they do not pollute and do not consume finite resources at a rate that is unsustainable. But it requires a radical shift - and the biggest barrier to that shift occurring, the financial markets, is barely even mentioned in discussions of the challenge.

READ MORE